- Manjaro: 21.0.7

Welcome back to the second part of the terminal basics series. Let’s do a short recap of what we learned in the first part. Our goal was to learn commands that allow us to do what we are used to do in a graphical interface:

- navigate between folders

- create/move/copy/remove files and folders

- search for files/folders

- install and uninstall software

- run software

The first two points were covered in the last blog post, where we learned in total nine commands:

pwd, ls, cd, touch, mkdir, cp, mv, rm, cat

Moreover, we learned things like the autocompletion or the “*” character. Both help to use the terminal conveniently. Check out the cheat sheet we made for you to get a quick overview of the commands. The topics of the last three points of the list above are covered in this post. Before we start, we prepared a small exercise to practice the commands of the previous post. We will use the solution in the remainder of this post, so make an effort!

Create the following folder structure:

+-- colors

| +-- blue.txt

| +-- red.txt

+-- houses

| +-- onehouse.txt

+-- info.txt

One possible solution is:

mkdir colors

mkdir houses

touch colors/blue.txt

touch colors/red.txt

touch houses/onehouse.txt

touch info.txt

Files addendum

In the last post, we already explained that you can create a file with the “touch” command and that you can print the content of a file with the “cat” command. However, we never told you how to actually fill a file with some content. The most obvious way to do that is to use a text editor. There are plenty of graphical and non-graphical editors from which you can choose your favorite. The question of which one is the best goes far beyond this post and will be covered in a later series of posts. For now, we will continue with an editor called nano. In our opinion, it is not the best editor you can use. So, why do we then still want you to know about it? First, it is very basic and easy to use. Therefore, it is good for the beginning. Second, it is installed on almost every Linux distribution. So, if you cannot or do not want to install anything, nano is always a choice to use.

Let’s fill the color files with price information. Open the file with the nano editor (do not forget to make use of autocompletion using the TAB key):

$ nano colors/blue.txt

Enter the following price:

price: 5

Exit the editor by pressing CTRL-X. You will be asked to save the file. Press “y” (yes) that you want to store the changes. Next, you have to enter a file name. Just press RETURN to keep the old file name.

Exercise:

Fill the files “red.txt” and “onehouse.txt” with a price of your choice.

File / Folder search

Now, we want to search for a file or a folder using the “find” command (probably you already noticed that command names are usually very intuitive). Let’s find the “red.txt” file:

$ find . -name "red.txt"

Found it? If you use the find command, you state the place where to search. In this case, the “.” refers to the folder you are currently in. Then, you can enter several search parameters, such as the file name. Do you remember the man page from the last post? You can use it to find other parameters. Next, we want to search for all files with the “.txt” ending. Can you guess how it works?

$ find . -name "*.txt"

Exercise:

Use the man page to find out how to search for all directories.

The solution is:

$ find . -type d

Of course, it is also possible to combine search parameters. We can search for all directories starting with a “c”:

$ find . -name "c*" -type d

The find command is brilliant to search for files and folders. Sometimes, however, it is also useful to search the content of files. In our example, we might want to search for the price information. Of course, you can also just open the file and have a look at it, but always have in mind that the examples are just for demonstration. In reality, there might be hundreds of files and maybe you do not even know in which file you can find the information you are looking for. To search the file content for the price, you can use:

$ grep -nr "price" .

Similar to the “find” command you can add some options and the place where to search. Note that in this case, the “.” is at the end of the command. The “r” option enables a recursive search, so all files in sub-folders are searched as well. The “n” option also gives you the line number as a result. Try to call it without the “n” option. Can you see the difference?

$ grep -r "price" .

“grep” is actually the last important command, for now, we learn to deal with files and folders. By adding the commands “find” and “grep”, we introduced to you in total eleven commands. Even though it is just a small piece of the whole Linux pie, it already provides you a lot of power. Additionally, we secretly showed you how to run a program! Did you notice? It is as simple as typing the name of the software like “nano”. Well, … to be honest, there is a bit more behind it. Let’s give you a bit more information in the following sections.

Software management

Linux distributions are usually shipped with preinstalled packages. Manjaro, for example, has basic software installed for your daily life, such as a text editor, a calculator, or a browser. At some point, however, you might want to install further software. If you are used to Windows, you probably would go to the website of the software distributor, download the software and run an installer. In Linux, you have many options to do it. A common way is to use something called a package manager.

Package Manager

What is a package manager? Well, it obviously manages your software packages. But what does that mean? It means that the package manager handles everything that deals with installing, upgrading, or removing software for you automatically. If you want to install a software package, you do not have to download it from a website. Just ask your package manager to do it for you. It knows where to get it. Sometimes software has a so-called dependency, so in order to run, it requires other software to be installed. The good news is that you do not have to deal with it. The package manager knows about it and installs all dependencies right away.

There is another cool thing. Imagine that you want to get a new software version. Maybe because there is a security bug in the old one or simply because the new version has a new feature you want to have. You can ask your package manager to update all your installed software. It can do a complete system update for you.

There exist many different package managers. We are going to introduce you to Pacman that is the standard package manager for Arch Linux distributions. Since Manjaro is based on Arch it is also commonly used there.

Pacman

Pacman is one of many available package managers. The good news is that all package managers work similarly. As always, you can check the manpage or help message to find out how to use it. Another option is to have a look into the Arch Wiki.

First, we should upgrade the whole system. It is recommended to do this from time to time because it will provide you with bug fixes, security fixes, and new features. We do it approximately once a month. However, there is also the possibility of getting new bugs. So, you should not upgrade when you are in a rush. Do not do it if you have a project deadline the next day. The command to do it is:

$ sudo pacman -Syu

You are probably asked to enter your system password. Depending on how many packages have to be installed, it might take some time. Usually, you will be asked for confirmation to update all packages. Sometimes, you are also requested to replace some files. You can answer everything with yes. Let’s discuss this command in detail. Can you remember the last post where we said that you are only allowed to write files that belong to your home directory? Now, you are trying to update files that belong to the system and not to you. “sudo” is a command that gives you root privileges. With this, you are allowed to change system files, so-called root files. Sudo is like Linux’ god mode, so use it with great care! Of course, not everyone should be allowed to do so. That’s why a password is required. The option “S” is used to install something. “y” is used to update the package database, from which Pacman has all its package information. According to the wiki page, it should only be used with the “u” option, which enables a complete system update.

Next, we want to install a new package called “vim”. It is another editor that we will use in later posts. Note that the package manager knows that two packages are required for it, which will be both installed with:

$ sudo pacman -S vim

Note: Do not randomly install packages. Try to only install packages you really need. If your system is messy once it is exhausting to clean up.

Simple, isn’t it? You can remove it again using:

$ sudo pacman -R vim

This time only vim itself is uninstalled and not the dependency vim-runtime. You can install it again and uninstall including the dependencies with the following command:

$ sudo pacman -S vim

$ sudo pacman -Rcns vim

Sometimes, you do not know the exact name of a package. At this point, a package search might be useful. Try to find all available vim packages:

$ pacman -Ss vim

Note: You do not need “sudo” here, because you do not write any files.

As we noted before, Pacman gets its information from a package database. This means that you can only install packages that are inside that database. You can imagine that not all packages that exist in the world are listed there. Consequently, the are packages you cannot install with Pacman. You can check the documentation of the package if it is inside another package manager or if you have to install it manually. We will come back to it in a later post.

Run your software

After we have learned how to install software, we now want to know how to run it. Actually, you already know how to do it. Do you remember how you run the editor “nano” by just typing its name into the terminal? That’s it! But let’s give you another example and have a closer look at the details.

You can open a firefox browser with:

$ firefox

Note: You also can install a browser of your choice using Pacman. Firefox is preinstalled with Manjaro, so we use it here.

A firefox window should open. If you want to exit firefox, you can either close the window or press CTRL-C inside the terminal. It will also exit if you close the terminal. Just have a try!

Note: CTRL-C is commonly used in the terminal to exit running programs.

In the case you closed firefox, start it again with the command above and take a look at the terminal. The cursor moved to the next line, but the line is blank. If you try to type a command like “ls” you will notice that you can type it, but it does not do anything. This is because you can only execute a new command after the previous one is completed. Here, firefox is still running. An easy workaround is to open a second terminal and run the “ls” command there. Have a try! It will work. However, there is something else you can do. Close firefox with CTRL-C and run it, again, with a tiny change:

$ firefox &

The “&” indicates that firefox shall run in the background. You will be prompted a number, which is the so-called process id (PID), and then you are able to enter further commands. If you want to exit firefox from the command line, you can do so using one of the following:

$ kill <PID>

$ killall firefox

The process id is the one you were shown when starting firefox. The “kill” command will, therefore, only kill that specific firefox process. The “killall” command will kill all firefox instances. You might wonder if you really need to take note of the process id, and the answer is, of course, no! Always remember that programmers are lazy! You can use the “ps” command to find the PID.

$ ps

There are many options you can add to this command. Check the man page for a full list. An often used command is

$ ps aux

which gives a list of all running processes. Since this list is usually long, you can search for a specific process. We already introduced the “grep” command to scan the content of files. Similarly, we can use it for any kind of text, such as the output of the “ps” command. We can use the pipe symbol (“|”) to connect the output of one command with the input of another command. So, here it’s not a file that is the input of “grep”. The input is the output of the “ps” command.

$ ps aux | grep firefox

You should be able to find your PID and also might see that firefox created child processes. If you kill the main process, you will kill all children as well. Damn … This world is so cruel! Sometimes it is also nice to use:

$ ps axjf

This will show you a process tree. You can see that firefox is a child of something called “bash”. We will talk about it in the next post, but it is essentially your terminal. Again, you can see the children of firefox.

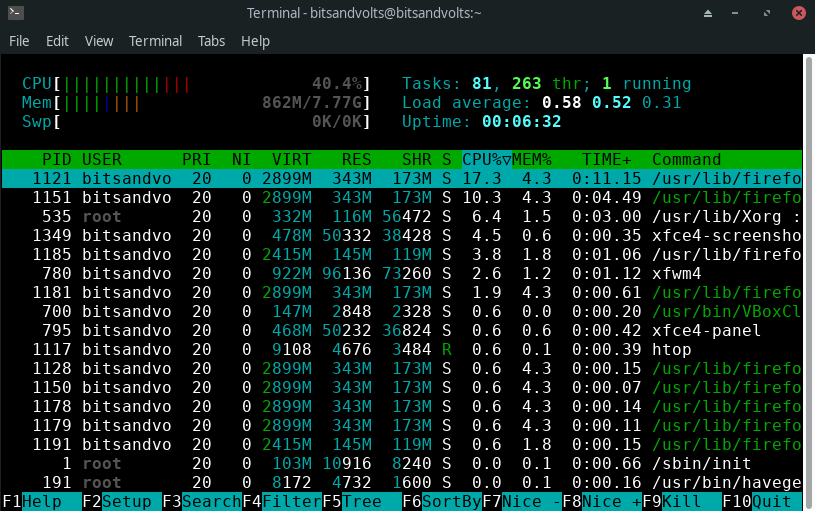

One last thing! Sometimes, it is useful to see how much CPU time each running process is using. A nice tool to do so is:

$ htop

Our single-core computer uses right now 862 MB of RAM and has a CPU utilization of around 40%. What about yours? If you have multiple cores, you can see the utilization per core. Exit “htop” using CTRL-C.

Real-life Example:

You notice that your computer is suddenly very slow. Especially in software development, a process might use a huge amount of computing power due to a bug. This can have a slowdown of your computer as a consequence. There could also be a process in the background that did not close as expected. With “htop”, you can identify such processes and kill them.

Summary

In the last two posts about the Linux terminal, we have already learned a total of 17 commands:

pwd, ls, cd, touch, mkdir, cp, mv, rm, cat, nano, find, grep, pacman, kill, killall, ps, htop

If you compare that with the number of vocabularies you have to learn for a foreign language, it is really not much. To be fair, there are many parameters you can use with the commands, but still, it should just take a little practice to learn them. And if you forgot something, there is still the man page where you can look it up. Of course, there are dozens of other commands. But with these, you can already accomplish most of your everyday tasks in Linux!

Like in the previous post, we summarized the commands in a cheat sheet that you can find in the GitHub repository of the “Getting Started” category. We put a lot of work and energy into our blog posts and the additional material, so please respect our terms of usage. Besides the commands you’ve also learned:

- Nano is one possible text editor

- The man page is a good place to look up commands

- A package manager handles software-related things for you

- Software can be dependent on other software

- It is recommended to run a system update from time to time

- The Arch Wiki is also a good resource

- You need root privileges to install or uninstall system software

- Programs can run as a background process

- The pipe symbol (“|”) can be used to connect the output of one command with the input of another

- Process IDs (PIDs) uniquely identify a process

In the next post, we will practice the commands and run our first script! Stay tuned, and don’t forget to follow us on Twitter!

Back to top ↑