We are glad that you are still following us on our journey! In our first post, we presented our personal Linux Computer Setup. Then, we demonstrated essential commands to control your computer in Terminal Basics and Terminal Basics II. Lastly, we implemented our first Basic Shell Script. In our opinion, this is all you need for a smooth beginner’s dive into the Linux world. But wait … There are two topics we mentioned in the previous post which we didn’t explain yet. Namely, we are talking about privileges and environment variables. We will cover the latter one in this post. The former one is covered in the upcoming post.

Environment Variables

You probably heard the two terms environment and variable before. The term variable should be familiar from your math class where you can have an equation like:

f(x) = x + 3

Do not worry! We do not want to do any math here. In the equation above you have

a variable called x, which can have different values like 2, 3, or 4.

Depending on that value, the outcome of f(x) will be different. So basically, a

variable has a name and a value and is capable of changing the behavior of

something. An environment is something more abstract. It is the conditions

that surround someone. For example, the place you are living in is the

environment for your daily life.

Now, let’s give an easy example of an environment variable. Imagine two different locations, one in Alaska and one in California. One possible variable for the environment could be the temperature. There you have it! An environment variable is a variable that describes an environment. Depending on the temperature you probably will wear different clothes. So, you will behave differently depending on the variable. But what does this has to do with computers? Similar to you wearing different clothes at different locations, a computer program might do something different in a different environment, which could be a different machine, different operating system, or simply a different setting. We are going to discuss some examples to make it clear.

List environment variables

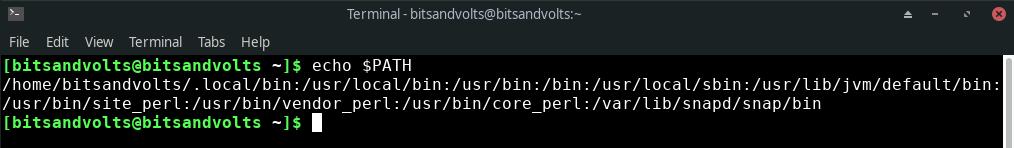

In the previous post, we already mentioned the PATH variable. It holds paths to directories where programs (executables) are stored. You can list the content of the variable using:

$ echo $PATH

As a reminder, the first $ indicates that it is a command for the terminal.

You do not have to type it into the command line. echo is the command to

display text in the terminal, the second $ indicates that the following is a

variable and PATH is the variable name. The output is a list of directories

separated by a colon:

Let’s try another example. Imagine you want to write a program that displays a

file in an editor. So far, we used nano as an editor, but can you be sure

that this is installed on the target machine? Maybe the user prefers another

editor! A better way would be to read the EDITOR variable and use the value as

editor. Unfortunately, there is no guarantee that the variable is set, but this

shall not be a topic for now. Check out how it is set for you:

$ echo $EDITOR

You can also list all your environment variables by using:

$ printenv

As we mentioned earlier, there is no guarantee that a specific variable is set

for your session. However, some common environment variables are set on most

Linux systems, such as PATH, EDITOR, SHELL, or USER. Of course, you can

change the value of any variable or create a new one as we will show in the

following.

Set environment variables

Let’s try to reuse the open_firefox.sh script from the last

post. In case, you do not

have it anymore, we are going to recreate it. Change to your home directory

(using an environment variable) and create the file:

$ cd $HOME # this is the same as `cd ~` or simply `cd`

$ nano open_firefox.sh

Enter the following script:

#!/bin/bash

# Print something to the terminal

echo "Greetings from Bits&Volts (bitsandvolts.org)"

# Open firefox

firefox -new-tab -url bitsandvolts.org \

-new-tab -url https://github.com/bitsandvolts/getting_started &

Add the correct privilege (this will be explained in the next post!):

$ chmod +x open_firefox.sh

In our last post, we have already seen that invoking the script as follows doesn’t work:

$ open_firefox.sh

The reason is that the script is not stored at a location that is part of the

PATH variable, so it cannot be found. Solution number one was to add the

script’s path, which is in this case your home directory, to the PATH

variable. This can be done by using the export command:

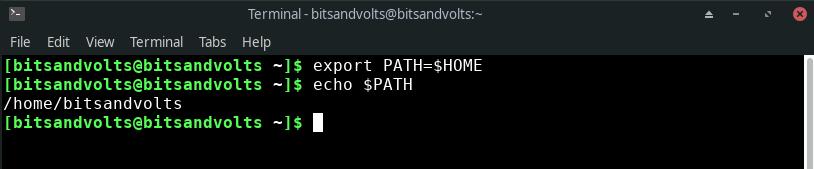

$ export PATH=$HOME

Here, you set the value of PATH to the content of the HOME variable. If you

display the content,

$ echo $PATH

you should see that it changed.

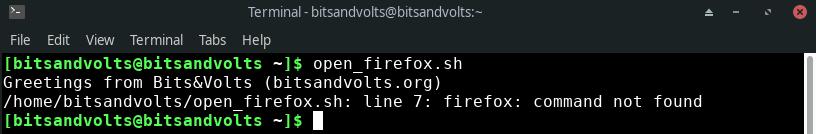

Now, try to run the script again as before:

$ open_firefox.sh

The script can be found, but now we get an error that firefox cannot be found?!

Hmm … It is the same script as we used in the last post and there it worked.

What went wrong? Can you guess? The answer is: we have overwritten the PATH

variable so that it solely consists of your home directory. Since firefox is not

located there, it cannot be found. By the way, also none of the Linux commands

we’ve learned will work anymore! Have a try:

$ ls

However, calling a command by its absolute path works:

$ /bin/ls

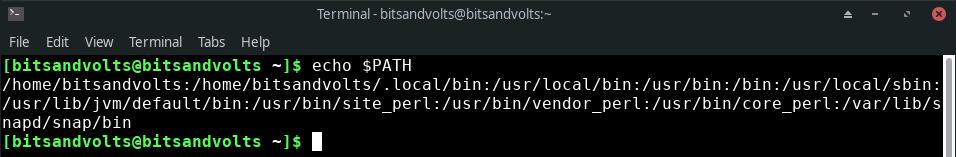

Does that mean, we broke our Linux?? Well, luckily no. Simply close and reopen

the terminal. Again, print the value of the PATH variable:

$ echo $PATH

You should see that it has its original value back. Whew. So, using the export

command as we did before, changes the value only for the current terminal

session. A new session will reinitialize all values. Now, we use the export

command slightly different:

$ export PATH=$HOME:$PATH

What does that do? Again we set the value of the PATH variable. We’ve already

mentioned that the directories in the PATH variable are separated by a colon.

So, we set the value to the home folder separated by a colon to the previous

value of the PATH variable. We simply add another directory. This time, the

script will work (and any other Linux command):

$ open_firefox.sh

Besides changing the value of existing variables, it is also possible to create new variables the same way:

$ export MY_VARIABLE=hello

You can then display the value of your newly created variable:

$ echo $MY_VARIABLE

Exercise:

Verify that you can also see your new variable using the printenv command.

Permanent change

There is one issue left. As we saw, the path setting stays active only for the

current session. What if you want to have it changed permanently? We do not

want to dive too deep into this for now, but we should mention that, when you

open a terminal, several scripts are executed automatically behind the scenes.

For example, ~/.bashrc (reminder: ~ is a shorthand for your home directory) is

one of them. When you want to extend the PATH variable whenever you open a new

terminal, you can put the export command into the bashrc. Open it:

$ nano ~/.bashrc

and add the export command to the end of the file.

$ export PATH=$HOME:$PATH

Save and close the file. Then, reopen your terminal and display the PATH

variable.

$ echo $PATH

Your home directory should be the first one. Now, you can instantly run the

open_firefox.sh script from every terminal you open, and from any location.

Keep the PATH variable in mind the next time you write a script, it can save

you a lot of time!

But … be aware of the fact that it is not a good way to always add more and more paths whenever you write a new script. This will most likely end up in a very messy system. Is there any good guideline? Hard to say! Let’s have a try … Generally, you can distinguish between two kinds of scripts and programs:

- A script/program that is only relevant for a specific project. This could be a script to delete temporary files in a project-specific folder. Here, the best way is to call the script by its absolute path, since it is nothing you need all the time.

- Scripts and programs you need all the time. An example could be the script

that opens your browser we implemented before. For this, a good solution is

to create a folder for all your self-made scripts, copy the script inside and

add it permanently to the

PATHvariable.

To be honest, this is a bit simplified. Reality might be more complex than this. There is also no clear rule of what is right or wrong. We often will face the situation that multiple solutions will work and it is not directly clear which is the better one. But don’t worry! It is easier to learn with some examples which we will do in later posts.

Summary

Alright! That is the whole magic about environment variables. Very likely, we are going to use them in future posts. In detail, we learned the following:

- Environment variables are variables that describe an environment

- An environment can be a different machine or setting

- You can display the content of a variable using echo

- $PATH holds directories with your executables

- Your home directory path is stored in $HOME

- $EDITOR can store the favorite editor

- Environment variables can be set using the export command

- There is no guarantee that a variable is set

- Variables are reinitialized for every new session

- For permanent changes, you can add the

exportcommand to a script like~/.bashrc

In the next post, we will talk about privileges! Stay tuned, and don’t forget to follow us on Twitter! Until then, we wish you all the best and a Happy New Year!

Back to top ↑